Originally posted on Gamasutra.

Introduction

Stop me if you’ve heard this one – a lone wolf with severe emotional issues saves the day and/or avenges a loved one by using a lot of violence.

How many times since games became digital have we experienced that story? How many times have we been a brown-haired white guy with a stubble? Don’t get me wrong, there is no inherent problem with these men or their story – it’s just that we have heard it so many times before. Retelling it yet again is uninspired and thereby bad writing.

Our medium keeps growing, and more and more people are experiencing our games. If we want to entertain them and make sure they keep coming back, we need to give them new stories. Other people’s stories. And we need to do this for at least two reasons.

Representation

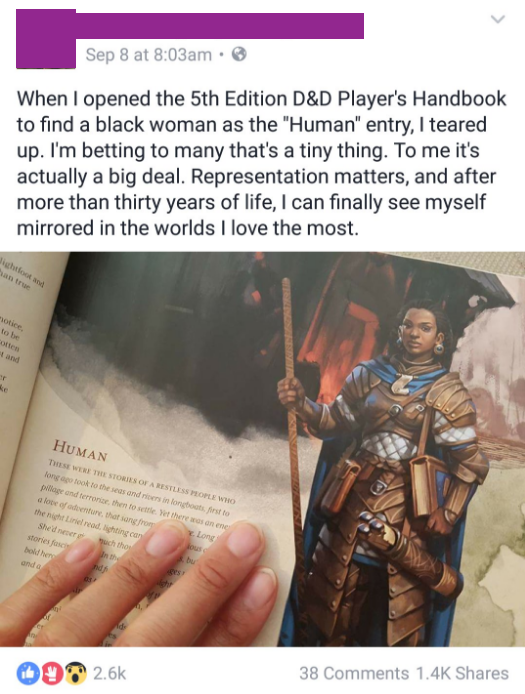

First off, more people need to be able to identify themselves with the characters they meet in our games. It is easy to dismiss representation for people who see themselves mirrored in what they play on a regular basis – but it really does mean a lot for others. If nothing else – if we can make more people feel seen and like they belong in the gaming community, we have a larger group of happy, returning customers. It is hardly rocket science.

The power of representation. (It’s a public post, but anonymized just in case.)

Impact

Secondly, we as an industry are still exploring what we can create when it comes to narrative. In order to keep doing so, we need to think outside the very small box we are currently using. If we look at literature for a second: there are probably several thousands of books about the Second World War, but a few stand out from the crowd and continue to be relevant more than half a century later. The reason why a book likeAnne Frank’s Diary is so important and memorable is because it tells a civilian’s – a young girl’s – story. Through it we can understand something about war, and maybe about humanity, that we cannot learn from yet another account of troop deployment in Normandy. How many games have portrayed the same or a similar landing of troops? But Anne Frank’s story has yet to be seen in a game. The closest thing we have is probably This War of Mine by 11 bit studios, and it did remarkably well on the market – possibly because it choose to portray a different aspect of war than most other games.

Tools

Creating a system for diversity

Sometimes, I don’t think we even do it on purpose – we are just so used to a white, straight cis man being the default. However, there are other paths you can tread. Let’s take a look at what Neil Druckmann has been quoted saying about Naughty Dog’s approach for Uncharted 4:

“When I’m introducing and describing a new character to our lead character concept artist, constantly she will ask, ‘What if it was a girl?’ And I’m like, Oh, I didn’t think about that. Let me think, does that affect or change anything? No? Cool, that’s different. Yeah, let’s do it.”

Even if I suggest calling adults women and not girls, we need more of this – creating a system for questioning the norm. Does it actually matter which gender this character is? If your gameplay is solid, do you really think you will lose sales because your protagonist steps away from the norm? Well, you might – but you might just as well gain even more.

Part of the cast of Shantee’s Choices, and/or a line to an ice-cream stand.

Character roster checklist

With all this in mind, I would like to present a checklist to use when designing characters for your game. Of course, you don’t have to make all your characters “unconventional” if you don’t want to – but when looking through your roster in the end, ask yourself if you have properly and respectfully represented these different human aspects. If not, is it a conscious choice you can motivate and stand by?

⬜ Age

⬜ Genders

⬜ Sexualities

⬜ Ethnicities

⬜ Body types

⬜ Physical ability

⬜ Mental ability

⬜ Beliefs/Religion

In practice

Now, let’s get a little more practical. For my own game Shantee’s Choices, one of the first things I did was to create a roster of all the important characters needed to tell the story. I started by googling reference images, collecting pictures of people that looked roughly like what I wanted in my game. Then I began putting similar images together to create characters, as well as contemplating who they were.

Character sheet

When the above was done, I filled out a character sheet for each emerging character, which contained the following information:

When the above was done, I filled out a character sheet for each emerging character, which contained the following information:

Tagline

One sentence that describes the character. Examples here are “the Broken Jester”, “the Artistic Street Rat” and “the Honorable Pirate”. If you can create a contradiction or elevator pitch with just a few words, you know that you have an interesting character.

Reference Images

Create a rough image of what the character looks like, by adding some reference material.

Name

All characters should have at least a given name and a family name. Nicknames, nom de plumes and so on are also a nice touch. What did their nana call them when they were growing up?

Age

Make sure that you have characters along the whole scale from young to old. Especially elderly women are unrealistically rare in games – don’t be afraid to try and change that.

Gender

What do people read the character as, and how do they define themselves? Remember not to limit yourself to binary definitions. If you are not familiar or comfortable with this, consider doing some research first.

Sexual/romantic preference

Characters should, just like physical people, have preferences when it comes to relations. Not everyone will automatically take their clothes off just because you have been nice to them, and some might even be completely uninterested in sex and/or romance.

Body type

Make sure you have characters that look different physically. Games are particularly bad at creating women that do not follow conventional beauty standards, which gives a very narrow and frankly boring scope to work with when it comes to character design.

Family

Everyone comes from somewhere. Far too often do we see characters that are completely disconnected from other people – why not create a protagonist with not only one but two living parents for once? That might even raise the stakes considerably if, say, the world needs to be saved.

Disposition

I chose to give all my characters a personality type based on DISC, to make sure they think and act differently. Are they extroverted or introverted, controlling or accepting? You can also use Myers-Briggs, if you like.

Fear

What is this character’s greatest fear – what do they want to avoid more than anything else? What, if anything, could make them snap if you put them too close to it? This could be anything from a phobia, such as spiders or clowns, or something more subtle, like succumbing to a hereditary disease or their children joining a certain faction.

Goals/dreams

What is it this character wants to achieve? What do they dream about when staring through the window on a rainy afternoon? Oh and world domination does not count. “Power because power” is not an interesting goal for a villain – power should, if anything, be viewed as a means to an end. Instead, consider what they are trying to accomplish. What is their end goal, that justifies their actions? No one is the bad guy of their own story.

Likes

Some things this character likes can be obvious and defining, such as a commanding officer enjoying order and an artist singing a lot. But I recommend also adding more personal things – stuff you would only learn if you really got to know them. Something like the smell of rain, bitter chocolate, or doodling.

Dislikes

What does this character not like? Just like above, add things all the way from the obvious to the deeply personal.

Supports

If there are factions of some kind in your game, note which one this character supports/is part of, and why. What, if anything, could make them change their mind? Where do they stand when it comes to politics? Anchor their ideas and beliefs in the world.

“Us”

Which group of people would this character go to lengths to protect? Would they do anything for one particular person, do they see themselves as the protector of a certain community, or are they the saviors of all of humanity? Basically, which omelett are they trying to make, and how many eggs are they willing to break for it?

Character inspiration

If this character is inspired by another character or maybe a historical person, note that here.

Sample dialog

How does the character talk? Add a few lines to show how they interact with other people.

Other

Here, you are free to add whatever you like that is unique to this character. What was their childhood like? Do they have any diagnoses or disabilities? Where and how do they live? Do they speak with an accent? This is where you can truly flesh out your character!

Penguins. Also, an iceberg.

“The Iceberg Theory”

When designing your characters, always keep in mind that most people will not drop their entire life history on you as soon as you meet them. Make sure that all the facts are there and that the characters reveal some when it makes sense – but never give away too much at the same time. Force the player to work a bit to get to know the inhabitants of your world.

Also, make sure that the first impression the character gives the player is not always what they will find when digging deeper. Many people hide things about themselves to strangers – maybe from fear of getting bullied, shame, regret, or something else – and only once they trust you will they start revealing who they truly are. In real life, getting to know people’s little oddities and faults is part of what builds real friendships.

Get input

If you feel like you want to make your characters more diverse, that’s great! Just try and make sure that you get it right. If you are writing a character with experiences you have not shared, ask for help. You might find that many people are more than happy to share their stories with you – especially if that means they will see themselves represented better in a game.

Also, do your homework! Read articles and books, listen to talks and panels. If you can research the hell out of WW2 tanks, you can research what it can be like to experience gender dysphoria as well.

Conclusion

If we are to tell new, interesting stories in games, we need to consider whose stories we are telling as well. Of course it’s easy for a solo indie dev to call for change and the situation may look very differently for a AAA writer – but with conscious choices and tools like the ones offered above, I believe that we can raise the bar for storytelling in games.

Thanks to Daniel Ström for proofreading!